Deciding on who/what to post about next can sometimes be hard. Not because I don’t know who/what to post, but because there are too many to choose from.

This gentleman, however, kept popping up everywhere I looked. In history magazines, #OnThisDay posts, etc.

So, who is this Alfred and what makes him so “Great”. I need to know.

Alfred was born to King Æthelwulf of Wessex and his first wife, Osburh, in the village of Wanating, now Wantage, in 849, the exact date is unfortunately unknown.

Alfred was the youngest of 5 siblings, 4 of them brothers. So, it seems very unlikely for him to one day become king.

In 853, Alfred is reported by the Anglo-Saxon Chronicles (a collection of records in Old English chronicling the history of the Anglo-Saxons), to have been sent to Rome where he was confirmed by Pope Leo IV who anointed him as king. Later, Victorian writers interpreted this as an anticipatory coronation in preparation for his eventual succession, but this seems unlikely since he still had surviving elder brothers.

A letter of Pope Leo IV shows that Alfred was made a “consul”, a misinterpretation of this appointment, deliberate or accidental, could explain later confusion.

It may also be based on Alfred accompanying his father on a pilgrimage to Rome around 854-855, where he spent some time at the court of King Charles the Bald of the Franks.

There is no record of his mother, Osburh. When I mean there is no record, I mean we don’t know if she died in 854 or she was rejected… What a time to be a woman.

I’m not sure when, but definitely before 854, Bishop Asser tells the story of how as a child Alfred won as a prize a book of Saxon poems, offered by his mother to the first of her children able to memorize it.

I’m not sure if this shows how smart he was, and maybe some bond with his mother. Or am I making something romantic out of nothing?

When Alfred and his father was returning from Rome, on 1 October 856, King Æthelwulf of Wessex married the daughter of the King Charles the Bald of the Franks’ daughter, Judith, who was aged 12 or 13 at the time.

The marriage was considered extraordinary by modern historians, as Carolingian princesses rarely married (especially foreigners), and were usually sent to nunneries. Judith was crowned queen and anointed by Hincmar, Archbishop of Rheims. This was also another odd thing, for West Saxon custom was a wife of a king was only that, the king’s wife and no other title.

When they arrived home, was deposed by his son Æthelbald. With civil war looming, the lords of the realm met in council to negotiate a compromise. Æthelbald would rule the western shires (i.e. historical Wessex), while his father, Æthelwulf, would rule in the east.

On 13 January 858, King Æthelwulf dies and was buried at Steyning in Sussex, but his body was later transferred to Winchester, probably by Alfred. He had no children with his second marriage to Judith.

Æthelwulf was succeeded by Æthelbald in Wessex and Æthelberht in Kent and the south-east. The status of a marriage with a Frankish princess was so great, that Æthelbald married his step-mother Judith, who was 14 or 15 at the time. Don’t worry if you find that wrong, Asser, who later became Bishop of Sherborne in the 890s, was said to have called it a “great disgrace”, and “against God’s prohibition and Christian dignity”. No mention on marrying a 12-year-old though…

However, two years later on 20 December 860, Æthelbald dies at Sherborne in Dorset. His brother, Æthelberht, becomes King of Wessex as well as Kent. This is because his two younger brothers, Æthelred and Alfred were too young to rule, but agreed that on his death, the younger brothers would inherit the whole kingdom.

After the death of Æthelbald, Judith sold her possessions and returned to her father, but two years later she eloped with Baldwin, Count of Flanders. Their son, also called Baldwin, marries Alfred’s daughter, Ælfthryth.

Alfred is not mentioned during the short reigns of his older brothers, Æthelbald and Æthelberht. In 865, with the accession of his brother, 18-year-old Æthelred, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicles describes the Great Heath Army. An army of Danes landing in East Anglia with the intent of conquering the four kingdoms that constituted Anglo-Saxon England.

With public life also beginning with Alfred at 16-years-old, Asser applied him the unique title of “secundarius”, which may indicate a position similar to the Celtic “tanist”, a recognised successor closely associated with the reigning monarch. This may have been endorsed by their father or by the Witan, a political institution assembled of the ruling class whose primary function was to advise the king. Its membership was composed of the most important noblemen in England. It was to guard against the danger of a disputed should Æthelred fall in battle. It was well known among other Germanic people to crown a successor as royal prince and military commander, such as among the Swedes and Franks, to whom the Anglo-Saxons were closely related.

In 868, Alfred married Ealhswith, daughter of a Mercian nobleman, Æthelred Mucel, ealdorman of the Gaini. The Gaini were probably one of the tribal groups of the Mercians. Ealhswith’s mother, Eadburh, was a member of the Mercian royal family.

Also in 868, Alfred and his brother Æthelred, were recorded in battle in an unsuccessful attempt to keep the “Great Heathen Army”, led by Ivar the Boneless out of the adjoining Kingdom of Mercia.

At the end of 870, the Danes arrived in his homeland and nine battles were fought in the following year, with varying outcomes. Though the places and dates of two of these battles have not been recorded.

31 December 870, a successful skirmish at the Battle of Englefield in Berkshire.

5 January 871, a severe defeat at the siege and Battle of Reading by Ivar’s brother, Halfdan Ragnarsson.

9 January 871, the Anglo-Saxons won a brilliant victory at the Battle of Ashdown on the Berkshire Downs, possibly near Compton or Aldworth. Alfred was credited with the success of this last battle.

The Saxons were defeated at the Battle of Basing on 22 January 871, and again on 22 March 871 at the Battle of Merton (perhaps Marden in Wiltshire or Martin in Dorset).

Shortly after, Æthelred died on 23 April 871 and leaving Alfred, not only succeeding to the throne, but the burden of defence. Even though Æthelred left two under-age sons, Æthelhelm and Æthelwold, it was in accordance with the agreement that Æthelred and Alfred had made earlier that year in an assembly at “Swinbeorg”. They had agreed that whichever of them outlived the other, would inherit the personal property that King Æthelwulf had left jointly to his sons in his will. Æthelred’s sons would receive only whatever property and riches their father had settled upon them, and whatever additional lands their uncle had acquired.

Given the ongoing Danish invasion, and the two boys being so young, Alfred’s accession probably went uncontested.

While preoccupied with the burial ceremonies for his brother, the Danes defeated the Saxon army in his absence at an unnamed spot, and then again in his presence at Wilton in May 871. The defeat at Wilton shattered any hope that Alfred could drive the invaders from his kingdom, forcing to make peace with them. It is not clear on what the terms were, but Bishop Asser claimed that the pagans agreed to vacate the realm and made good their promise.

The Viking army did withdraw from Reading in autumn of 871 to take up winter residence in Mercian London. Although it was not mentioned by either Asser, or the Anglo-Saxon Chronicles; Alfred probably also paid the Vikings gold to leave, much as the Mercians were to do in the following year.

Archaeological discoveries dating to the Viking occupation of London in 871-872, have been excavated at Croydon, Gravesend, and Waterloo Bridge. The findings hint at the cost involved in making peace with the Vikings. For the next five years, the Danes occupied other parts of England.

The Danes under their new leader, Guthrum, slipped past the Saxon army and attached and occupied Wareham, Dorset in 876. Even though Alfred blockaded them, he was unable to take Wareham by assault. Thus, he negotiated a peace which involved an exchange of hostages and oaths, which the Danes swore on a “holy ring” associated with the worship of Thor. However, the Danes broke their word and, after killing all the hostages, slipped away under cover of night to Exeter, Devon.

Alfred blockaded the Viking ships in Devon and, with a relief fleet having been scattered by a storm, the Danes were forced to succumb, withdrawing to Mercia.

In January 878, the Danes made a sudden attack on Chippenham, Wiltshire, a royal stronghold in which Alfred had been staying over Christmas. Most of the people were killed, leaving Alfred and a band of people to escape their way into the woods and swampland. After Easter, they made a fort at Athelney in the marshes of Somerset.

From his fort at Athelney, Alfred was able to mount an effective resistance movement, rallying the local military from Somerset, Wiltshire and Hampshire.

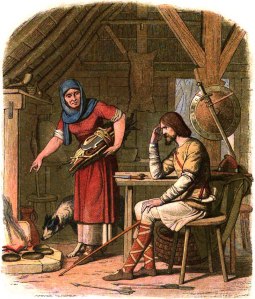

There is a legend originated from 12th century chronicles, tells of how Alfred first fled to the Somerset Levels. He was given shelter by a peasant woman who, unaware of his identity, left him to watch some wheaten cakes she had left cooking on the fire. Preoccupied with the problems of his kingdom, Alfred accidently let the cakes burn. When the woman returned, she scolded Alfred for his neglect.

Whether this story is true or not, it’s fascinating none the less.

In the seventh week after Easter, 4-10 May 878, Alfred rode to Egbert’s Stone east of Selwood where he was met by the people of Somerset, Wiltshire and west of Southampton Water, who were rejoiced to see him.

Alfred’s emergence from the marshland stronghold was part of a carefully planned offensive that entailed raising the fyrds of three shires. This meant not only that Alfred had retained the loyalty of ealdormen, royal reeves and king’s thegns, who were charged with levying and leading these forces, but that they had maintained their positions of authority in these localities well enough to answer his summons to war. Alfred’s actions also suggest a system of scouts and messengers.

Alfred won a pivotal victory in the Battle of Edington, which may have been fought near Westbury, Wiltshire. He then pursued the Danes to their stronghold at Chippenham, starving them to submission. One of the terms for their surrender was that Guthrum to be converted to Christianity.

Three weeks later, Guthrum and 29 of his chief men, were baptised at Alfred’s court at Aller, near Athelney, with Alfred receiving Guthrum as his spiritual son.

According to Asser; “The unbinding of the Chrisom took place with great ceremony eight days later at the royal estate at Wedmore”.

While at Wedmore, Alfred and Guthrum (now christened Æthelstan after he converted), negotiated the Treaty of Wedmore (which some historians have termed), but it was to be some years after the cessation of hostilities that a formal treaty was signed. Under the Treaty of Wedmore, Æthelstan (Guthrum) was required to leave Wessex and return to East Anglia.

Consequently, in 879 the Viking army left Chippenham and made its way to Cirencester. The formal Treaty of Alfred and Guthrum, preserved in Old English in Corpus Christi College, Cambridge (Manuscript 383), and in a Latin compilation known as “Quadripartitus”, was negotiated later, perhaps in 879 or 880, when King Ceolwulf II of Mercia was deposed.

That treaty divided up the kingdom of Mercia. By its terms the boundary between Alfred’s and Æthelstan’s (Guthrum) kingdoms was to run up the River Thames to the River Lea, follow the Lea to its source (near Luton), from there extend in a straight line to Bedford, and from Bedford follow the River Ouse to Watling Street.

In other words, Alfred succeeded to Ceolwulf’s kingdom consisting of western Mercia, and Æthelstan (Guthrum) incorporated the eastern part of Mercia into an enlarged kingdom of East Anglia (henceforward known as the Danelaw). By terms of the treaty, moreover, Alfred was to have control over the Mercian city of London and its mints, at least for the time being.

The disposition of Essex, held by West Saxon kings since the days of Egbert, is unclear from the treaty though, given Alfred’s political and military superiority, it would have been surprising if he had conceded any disputed territory to his new godson.

With the signing of the Treaty of Alfred and Æthelstan (Guthrum), around 880 when Æthelstan (Guthrum) people began settling in East Anglia, Æthelstan (Guthrum) was no longer a threat. The Viking army, which had stayed at Fulham during the winter of 878-879, sailed for Ghent and was active on the continent from 879-892.

Even though Æthelstan (Guthrum) was no longer a threat, Alfred was still forced to contend with a number of Danish threats. A year later in 881, Alfred fought a small sea battle against four Danish ships. Two of the ships were destroyed and the others surrendered to Alfred’s forces.

Similar small skirmishes with independent Viking raiders would have occurred for much of the period, as they had for decades.

In 883, which is a debatable date, because of Alfred’s support and his donation of alms to Rome, received a number of gifts from Pope Marinus. Among the gifts was reputed to be a piece of the “true cross”, a great treasure for the devout Saxon king. According to Asser, because of Pope Marinus’ friendship with Alfred, the pope granted an exemption to any Anglo-Saxon residing within Rome from tax or tribute.

I wonder if he was “rewarded” because of his push of Christianity against the pagans. Forcing people to change their religion… I always find something wrong with this, but even though I can argue and fume, this did happen a very long time ago.

In 885, there was another skirmish with the Vikings in Kent, an allied kingdom in South East England. It was also quite possibly the largest raid since the battles with Æthelstan (Guthrum).

Asser’s account of the raid places the Danish raiders at the Saxon city of Rochester, where they built a temporary fortress in order to besiege the city. Alfred’s response was to lead an Anglo-Saxon force against the Danes who, instead of engaging the army of Wessex, fled to their beached ships and sailed to another part of Britain.

Supposably, the retreating Danish force left Britain the following summer.

Not long after the failed Danish raid in Kent, Alfred dispatched his fleet to East Anglia. The reasons for this are unclear, but Asser claims that it was for the sake of plunder. After traveling up the River Stour, the fleet was met by Danish vessels that numbered between 13 and 16, and battle ensued.

The Anglo-Saxon fleet were victorious, but while leaving the River Stour, was attacked by a Danish force at the mouth of the river. The Danish fleet defeated Alfred’s fleet, which might’ve been weakened in the previous battle.

The following year in 886, Alfred reoccupied the city of London and set out to make it habitable again.

He entrusted the city to the care of his son-in-law, Æthelred, ealdorman of Mercia. He was the husband of Alfred’s first daughter, Æthelflæd.

The restoration of London progressed through the latter half of the 880s and is believed to have revolved around: a new street plan; added fortifications in addition to the existing Roman walls; and, some believe, the construction of matching fortifications on the south bank of the River Thames.

This is also the period in which almost all chroniclers agree that the Saxon people of pre-unification England submitted to Alfred. But, this was not the point at which Alfred came to be known as King of England. In fact, he would never adopt the title himself…

Between restoration of London and the resumption of large-scale Danish attacks in the early 890s, Alfred’s reign was rather uneventful. The relative peace of the late 880s was marred by the death of Alfred’s sister, Æthelswith, while she was en route to Rome in 888. That same year, the Archbishop of Canterbury, Æthelred, also died.

One year later, Æthelstan (Guthrum), Alfred’s former enemy and king of East Anglia, died and was buried in Hadleigh, Suffolk.

Æthelstan (Guthrum) passing changed the political landscape for Alfred. The resulting power vacuum stirred up other power-hungry warlords eager to take his place in the following years. The quiet years of Alfred’s life were coming to a close a war was on the horizon.

In the autumn of 892 or 893, the Danes attacked again.

Finding their position in mainland Europe precarious, they crossed to England in 330 ships in two divisions. Majority of them entrenched themselves at Appledore, Kent, while the rest under Hastein, to Milton, also in Kent. The invaders brought their wives and children with them, indicating a meaningful attempt at conquest and colonisation. Alfred, in 893 or 894, took up a position from which he could observe both forces.

While he was in talks with Hastein, the Danes at Appledore broke out and struck north westwards. They were overtaken by Alfred’s eldest son, Edward, and were defeated in a general engagement at Farnham in Surrey. The took refuge on an island at Thorney, on the River Colne, between Buckinghamshire and Middlesex, where they were blockaded and forced to give hostages and promise to leave Wessex. They went then to Essex, and after suffering another defeat at Benfleet, joined Hastein’s force at Shoebury.

While Alfred was on his way to relieve his son at Thorney, he heard that the Northumbrian and East Anglian Danes were besieging Exeter and an unnamed stronghold on the North Devon shore. Alfred at once hurried westward and raised the Siege of Exeter. The fate of the other unknown stronghold was not recorded. Or was, and is lost, for reasons we will not know.

The force under Hastein set out to march up the Thames Valley, probably with the idea of assisting their friends in the west. When they arrived, they were met by a large force under the three great ealdormen of Mercia, Wiltshire and Somerset, forcing to head off to the northwest, being finally overtaken and blockaded at Buttington.

An attempt to break through the English lines was defeated. However, those who escaped, retreated to Shoebury.

After they gathering reinforcements, they made a sudden dash across England and occupied the ruined Roman walls of Chester. The English did not attempt a winter blockade, but contented themselves with destroying all the supplies in the district.

Early in 894 or 895, lack of food obliged the Danes to retire once more to Essex. At the end of the year, the Danes drew their ships up the River Thames and the River Lea, fortifying themselves twenty miles (32km) north of London.

A direct attack on the Danish lines failed, but later in the year Alfred saw a means. Obstructing the river to prevent any way of getting to the Danish ships. Realising they were outmanoeuvred, the Danes struck off north-westwards and wintered at Cwatbridge near Bridgnorth.

The next year (896 or 897), they gave up the struggle. Some retired to Northumbria, some to East Anglia. Those who had no connections in England, withdrew back to the continent.

I’ve talked a lot about Alfred’s accomplishments against the Danes, but nothing about his appearance and character.

Asser wrote in his book, Life of King Alfred;

Now, he was greatly loved, more than all his brothers, by his father and mother—indeed, by everybody—with a universal and profound love, and he was always brought up in the royal court and nowhere else. … [He] was seen to be more comely in appearance than his other brothers, and more pleasing in manner, speech and behaviour … [and] in spite of all the demands of the present life, it has been the desire for wisdom, more than anything else, together with the nobility of his birth, which have characterized the nature of his noble mind.

He also mentioned that Alfred did not learn to read until he was twelve-years-old or later, which he described as “shameful negligence” of his parents and tutors.

Alfred was an excellent listener and had an incredible memory. Retaining poetry and psalms very well.

Alfred is also noted to be carrying around a small book, probably a medieval version of a small pocket notebook. It contained psalms and many prayers that he often collected.

Asser writes; “He collected in a single book, as I have seen for myself; amid all the affairs of the present life he took it around with him everywhere for the sake of prayer, and was inseparable from it”.

He was also described as an excellent huntsman, against whom nobody’s skills could compare.

Maybe because he was the youngest, he was very open-minded, being an early advocate for education. His desire for learning could have come from his early love of English poetry and inability to read or physically record it until later in life.

I also mentioned a couple of his children, but in total Alfred and his wife Ealhswith had five or six children; Edward the Elder, who would succeed his father as king; Æthelflæd who became Lady (ruler) of the Mercians in her own right; and Ælfthryth who married Baldwin II the Count of Flanders.

On 26 October 899, Alfred died. How he died is still unknown, although he suffered throughout his life with a painful and unpleasant illness. Asser gave a detailed description of Alfred’s symptoms and this has allowed modern doctors to provide a possible diagnosis.

It is thought that he had either Crohn’s disease, a type of inflammatory bowel disease, or haemorrhoidal disease. His grandson, King Eadred, seems to have suffered from a similar illness.

Alfred was originally buried in the Old Minster in Winchester, but four years after his death, he was moved to the New Minster (perhaps built specially to receive his body).

When the New Minster moved to Hyde, a little north of the city, in 1110, the monks were transferred to Hyde Abbey along with Alfred’s body and those of his wife and children, which were presumably interred before the high alter.

Soon after the dissolution of the abbey in 1539, during the reign of Henry VIII, the church was demolished, leaving the graves intact.

The royal graves and many others were probably rediscovered by chance in 1788, when a prison was being constructed by convicts on the site. Prisoners dug across the width of the alter area in order to dispose of rubble left at the dissolution. Coffins were stripped of lead, and bones were scattered and lost. The prison was demolished between 1846 and 1850.

Further excavations in 1866 and 1897 were inconclusive. In 1866, amateur antiquarian John Mellor, claimed to have recovered a number of bones from the site which he said were those of Alfred. These later came into the possession of the vicar of nearby St Bartholomew’s Church who reburied them in an unmarked grave in the church graveyard.

Excavations conducted by the Winchester Museums Service of the Hyde Abbey site in 1999 located a second pit dug in front of where the high altar would have been located, which was identified as probably dating to Mellor’s 1886 excavation. The 1999 archaeological excavation uncovered the foundations of the abbey buildings and some bones. Bones suggested at the time to be those of Alfred proved instead to belong to an elderly woman.

In March 2013, the Diocese of Winchester exhumed the bones from the unmarked grave at St Bartholomew’s and placed them in secure storage. The diocese made no claim they were the bones of Alfred, but intended to secure them for later analysis, and from the attentions of people whose interest may have been sparked by the recent identification of the remains of King Richard III.

The bones were radiocarbon-dated, but the results showed that they were from the 1300s and therefore unrelated to Alfred.

In January 2014, a fragment of pelvis unearthed in the 1999 excavation of the Hyde site, which had subsequently lain in a Winchester museum store room, was radiocarbon-dated to the correct period. It has been suggested that this bone may belong to either Alfred or his son Edward, but this remains unproven.

Alfred commissioned Asser to write his biography, and as you’ve seen in his comments, obviously to emphasize on his best attributes.

Later, medieval historians, such as Geoffrey of Monmouth, also reinforced Alfred’s favourable image. By the time of the Reformation, Alfred was seen as being a pious Christian ruler who promoted the use of English rather than Latin, and so the translations that he commissioned were viewed as untainted by the later Roman Catholic influences of the Normans. Consequently, it was writers of the sixteenth century who gave Alfred his epithet as ‘the Great’ rather than any of Alfred’s contemporaries. The epithet was retained by succeeding generations of Parliamentarians and empire-builders who saw Alfred’s patriotism, success against barbarism, promotion of education and establishment of the rule of law as supporting their own ideals.

I find that fascinating, because I have always wondered who gives the title of “Great”.

A number of educational establishments are named in Alfred’s honour. These include:

The University of Winchester created from the former “King Alfred’s College, Winchester” (1928 – 2004)

Alfred University and Alfred State College in Alfred, New York. The local telephone exchange to Alfred University is 871 in commemoration of Alfred’s ascension to the throne.

In honour of Alfred, the University of Liverpool, created a King Alfred Chair of English Literature.

King Alfred’s Academy, a secondary school in Wantage, Oxfordshire, the birthplace of Alfred.

Okay, as you can guess, there are a few places named after Alfred. If you want to know more, just Google it…

As well as establishments naming after him, there are many statues dedicated to Alfred the Great. They are located at;

Alfred University (New York), USA

Pewsey, Wiltshire, England

Wantage, Oxfordshire, England

Winchester, Hampshire, England

Cleveland, Ohio, USA